In the previous article, I asserted that clichés ensnare the composer, placing them at the mercy of the symbols they’re deploying. Well. This isn’t necessarily true. Well, it is. But only insofar as the composer doesn’t want to be ensnared. As previously stated, when one invokes a cliché, one never reaches the destination, unless that destination is the street-sign itself. In other words, if your piece is about street-signs, use the damn street-sign. If the thing the artist is trying to reference is the cliché itself, then there is no better way to do that than to invoke it.

This is not an invocation to be made lightly, however. One does not simply dim the lights, set up the candles, paint a pentagram on the floor, break out the ouija board, and summon a cliché into one’s living room on a Wednesday night. Nor should the above reasoning be deployed retroactively to justify artistic choices that simply weren’t thought through. Rather, the most effective uses of cliché are often when an artist is saying something original about the cliché, about the medium, about the repertoire, about the cultural context, about what the cliché says about us, etc.1Though neither bolded nor italicized, the word “original” is key to this idea. It would do the artist little good to seek shelter from one cliché by leaping into the gaping maw of another. More on this problem later in the article.

The Meta-Reference: Æsthetic Distancing and Brechtian Alienation

When a self-referential symbol (i.e., a cliché) is situated in an æsthetic frame that extends “from this artifact [—i.e., the cliché itself—] to the entire system of the media, [and then] forms or implies a statement about…the medium/system referred to,” it is termed a Meta-reference.2Werner Wolf, “Metareference across Media: The Concept, its Transmedial Potentials and Problems, Main Forms and Functions,” in Metareference across Media: Theory and Case Studies, ed. Werner Wolf, Katharina Bantleon, Jeff Thoss, and Walter Bernhart, (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009), 31.

In cases like these, the artist often needs to strongly reference the cliché itself. And since all clichés do is reference themselves—and since they are some of the strongest symbols that exist—it just makes sense to use them.

Through this method, the artist distances themself from the vortical subject matter by encapsulating it within another symbol that lies “on a logically higher level, a ‘meta-level’”3Ibid. than the cliché itself. In other words, if the work we’re creating is, say, about a certain cliché, then it’s as if we’re observing that cliché from afar, within the broader context of the repertoire. This is contrasted with a piece that simply haphazardly invokes a cliché, which we would observe up-close, caught in its drifts, within the narrow contextual confines of that piece alone.

It’s the difference between taking a class and watching someone teach a class; between attending a play and walking by a bunch of people putting on a play. For each of these two examples, in the latter case the observer is one layer removed from the action at hand, looking at it from the outside in. This layer of separation creates a

corresponding ‘meta-awareness’…in the recipient, who thus becomes conscious of both the medial (or ‘fictional’ in the sense of artificial and, sometimes in addition, ‘invented’) states of the work under discussion and the fact that media-related phenomena are at issue, rather than [non-meta] references to the world outside the media.4Ibid.

That quote is a little dense, but basically, the observer (i.e., the listener) becomes aware that the work is dealing with subject matter that involves its own medium (i.e., the instrument, the repertoire, etc.), as opposed to something outside of that medium (e.g., love, longing, God, death, political subjects, etc.). Perhaps more importantly, however, the listener becomes acutely aware of the “medial state” of the work of art—that the piece is an invented, fictional, or otherwise artificial work. Of art. It’s as though the work of art has been affixed with a big, albeit somewhat long-winded, neon sign saying,

I am a work of art! I am not a new reality, but, a work of artifice embedded in your reality.

What was once a swirling mælstrom is now just a fridge magnet in the shape of a spiral. And the broader work of art—in which the cliché is embedded—is not the magnet, but a photograph of the kitchen. To reinvoke our general relativity metaphor, we’re not affected by the gravity eddies of the cliché-singularity because we’re not embedded in its spacetime, but rather observing its entire universe from the outside in.

• • •

In many ways, meta-reference is a kind of fourth wall-breaking, but instead of reminding the audience that they’re an audience by directly addressing them as such—Ferris Bueller-style—you’re simply destroying their suspension of disbelief. You’re reminding the audience they’re an audience by telling them that you are something that necessarily implies their existence: i.e., an artificial work of art—a made-up character, which implies a play, which implies an audience.

This distancing, or alienation, of the audience from the subject matter by intentionally disrupting their suspension of disbelief was popularized—and some would say perfected—by theatre practitioner Bertolt Brecht.

Verfremdungseffekt—a.k.a distancing effect, a.k.a alienation effect, a.k.a. estrangement effect, a.k.a. defamiliarization effect, a.k.a. distantiation5The exact English rendering of this agglutinous German word is a matter of some disagreement.—is an approach to stagecraft whereby a variety of techniques are used to deliberately disrupt the audience’s suspension of disbelief and remind them, “You are watching a play!”

Verfremdungseffekt includes such practices as:

- constantly addressing the audience directly (to the point of never even pretending as though there were a fourth wall to begin with);

- acting in an excessively ironic, self-observant, or sarcastic manner;

- double-casting actors & characters;

- having actors move set pieces and change their costumes in full view of the audience;

- speaking stage directions out loud;

- explaining the action of each scene before it happens (destroying the expectation game)

- making backstage elements visible to the audience (e.g., trusses, prop tables, actors as they get ready to go on stage);

- making technical elements visible to the audience (e.g., lights, cables, sound equipment, technicians);

- creating sound effects with the voice, by someone situated in full view of the audience;

- episodic scene structure (often involving long spans of time between episodes);

- distant geographic or temporal settings;

- and, of course, the use of thematically-dissonant6That is to say, dissonance between media (i.e., music and some other medium) in the multimedia (in this case, theatrical) work—e.g., quirky, jolly music and dance paired with harrowing text about the need to prostitute oneself or face starving to death. This is not to be confused with dissonance between elements within a single medium—e.g., harmonic dissonance, melodic angularity, poetic enjambment, slant rhyme, narrative tension, complementary colors, etc. For more on consonance and dissonance between musical and non-musical media, I, once again, recommend Daniel Albright’s Untwisting the Serpent. music—for Brecht, in collaboration with composer Kurt Weill—that comments ironically on the action of the play.

For Brecht, these techniques—and Epic Theatre, the broader theatrical style in which they were deployed—were used to snap the audience out of becoming so emotionally attached to the characters and the story that they lost sight of the work’s politically didactic qualities. He wanted to create theatre that would not merely entertain audiences, but that would compel them to get woke! As such, the play was constantly reminding them that it was critiquing systems of power in the real world and constantly asking the audience to critique those systems as well.

A full discussion of Verfremdungseffekt and Epic Theatre—its associated genre—would go beyond the scope of this article,7b e y o n d t h e s c o p e but the important point here is that Brecht used these techniques to remind the audience that what they were watching was not a performance, but a performance of a performance. Contrary to Shakespeare’s play within a play, however, Brecht sought to create a play without a play, or a play outside of a play—an inside-out play. And while Brecht used the Verfremdungseffekt within the context of Epic Theatre (i.e., for politically or ethically didactic purposes), the Verfremdungseffekt can be abstracted and viewed simply as a way of changing the frame that bounds the æsthetic experience.

Just as Brecht extends this frame such that it spills out from the proscenium to engulf the entire theatre—wherein the onstage action is a performance embedded within that larger boundary—, an artist seeking to distance themself from an invoked cliché might extend the æsthetic frame of their work to span the entire repertoire, such that the audience is experiencing a work of art about the repertoire wherein the original artifact (i.e., the invoked cliché) is a character, a symbol, a motif, a gesture, et cetera.

This broadening of the æsthetic frame is readily seen in meta-referent works of literature and visual art as well, especially those by such Modernists as Vladimir Nabokov and Marcel Duchamp.

Pale Fire: From the Depths of the Abyss, We Journey into Metafictive Bliss

William Shakespeare, Timon of Athens, in Timon of Athens, ed. Anthony Dawson and Gretchen Minton (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2008), 1.3.432-433. References are to act, scene, and line. Accessed January 9, 2021.

You might say “réalisme bucolique”.

So here we find,

Just like the ones in this affected speech. were the age-old norm

The rhythm here, in fact, is three on five.

Let’s take a breath.

A broader gaze

• • •

QED.

Similar to Pale Fire—which critically analyzed through literature the critical analysis of literature—the anti-art of the Dadaists inherently critiqued the repertoire of the day—i.e., the accepted norms ascribed to art around the turn of the century—, and thus often deployed clichés, vandalizing and mutilating them within the broader frame of the cultural context in which they originated.

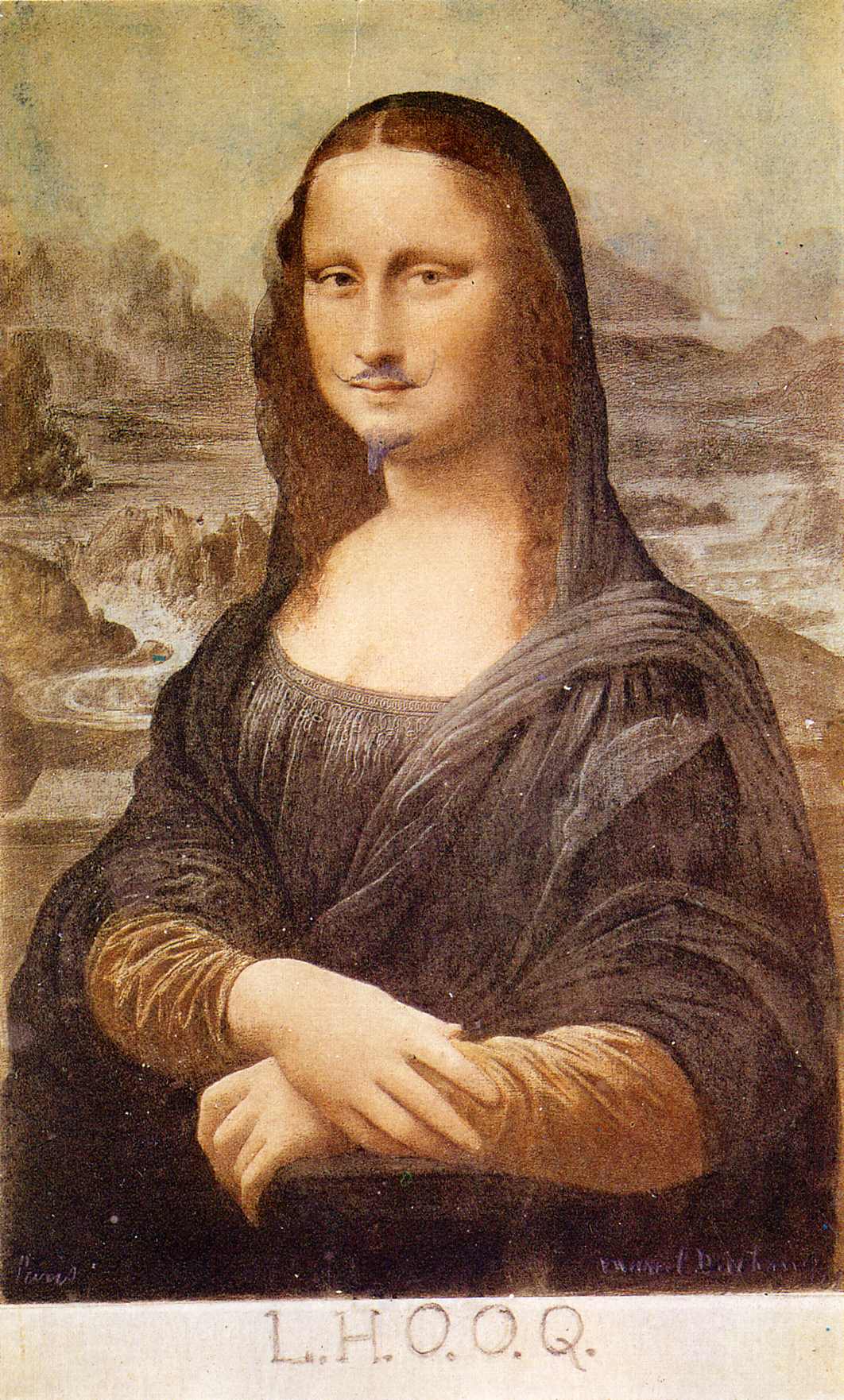

Perhaps the most salient example of this kind of dismanglement is L.H.O.O.Q., one of Marcel Duchamp’s delicious Readymades.

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q., 1919-20.

Pencil on a Postcard,

The Readymades are a group of works consisting of prefabricated—often mass-produced—found-objects reframed by Duchamp to become works of art, especially those he produced from 1913 to 1921.16Grove Art Online, s.v. “Ready-made,” by Matthew Gale, accessed 12 Jan 2021. Some Readymades, such as the Bottle Rack (1914) were presented in their unaltered form. Others such as Fountain (1917)—perhaps the most notorious of the Readymades—included slight modifications, i.e., the signature “R. Mutt” and year of creation inscribed on the side. Others still were created through the amalgamation of several “readymade” objects, e.g., Bicycle Wheel (1913), which mounted on a stool the front wheel of a bicycle. While art scholars—and even Duchamp himself17“Asked in an interview, ‘What is a readymade,’ Duchamp’s first response was to laugh. When this laughter subsided, he gave an example: Mutt’s Fountain. Asked to expand upon the matter, he turned to other possibilities for readymades. He noted that there was the ‘assisted readymade’ (ready-made aidé), and gave as an example his mistreated Mona Lisa.”

Leland de la Durantaye, “Readymade Remade: Pierre Pinoncelli and the legacy of Duchamp’s ‘fountains,’” Cabinet, Fall 2007,—have created sub-phyla of Readymades into which the works may be categorized based on the nature and amount of modifications the artist has exacted upon the original mass-produced object,18Notably: Pure Readymades, objects unaltered by the artist; Assisted Readymades, objects made by combining two or more pre-existing objects; and Rectified Readymades, objects to which some traditionally-artistic medium has been added (e.g., oil paint, graphite, gouache, etc.). there is some disagreement as to exactly how certain works should be classified.19Encyclopædia Britannica considers Fountain to be a so-called Pure Readymade*, while Grove Art Online states that it may be considered an Assisted Readymade due to the signature “R. Mutt” applied to the work.† The application of paint to the piece, however,—as opposed to its combination with some other pre-made object—would seem to designate it a Rectified Readymade. Even the work in question, L.H.O.O.Q., is regarded by Grove Art Online and the Norton Simon Museum‡ as a Rectified Readymade, while Duchamp himself has been quoted describing it as Assisted (see note 17)! In the end, it’s clear that the exact taxonomy of these objects is subjective and completely beside the point: such classification serves not to impose a rigid labeling system upon a diverse group of works created before such a system was even considered by the artist, but to simply highlight for the viewer—subjectively—certain differences among the objects that may aid with their æsthetic interpretation.

* Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. “Ready-made,” accessed 12 Jan 2021.

† Grove Art Online, “Ready-made.”

‡ “L.H.O.O.Q. or La Joconde,” Norton Simon Museum, accessed 12 Jan 2021.

The work under discussion, L.H.O.O.Q. was created from a cheap postcard of La Joconde onto which Duchamp drew with a pencil—an equally cheap writing implement—a mustache and goatee, and affixed the aforementioned title. Duchamp’s irreverent play on words may immediately register for the francophones among us: L.H.O.O.Q., when spoken aloud in French as /ɛlaʃoʔoky/ is phonetically equivalent to the phrase Elle a chaud au cul. Transliterated into English, this yields “Her ass is hot,” but a more colloquial rendering would be, “She’s down to fuck.”20The phrase Elle a le feu au cul—literally meaning “her ass is on fire”—is the more common variant of this vulgarism,§ but if the chaud fits, wear it.

§ Wiktionary, s.v. “avoir le feu au cul,” accessed 16 Jan 2021; Audrey Langevin, “Avoir Le Feu Au Cul,” Les Dédexpressions, last modified 13 Oct 2019, accessed 16 Jan 2021.

At face value,21No pun here, folks. Carry on. L.H.O.O.Q. seems like a “blatant attack on traditional values.”22 Paul N. Humble, “Anti-Art and the Concept of Art,” chap. 19 in A Companion to Art Theory, ed. Paul Smith and Carolyn Wilde (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), 247. By appropriating and disfiguring “one of the most celebrated masterpieces of European Art,”23ibid. Duchamp is, on a global level, critiquing the standards by which art is evaluated by audiences of his day—and even probing their definitions of what constitutes art to begin with. But on a local level, he’s also drawing attention to the fact that La Gioconda has permeated European culture so deeply, so inextricably, that it has become both a self-referential symbol—i.e., a cliché—and an embodiment of the very concept of cliché.

In other words, for Duchamp, not only has the Mona Lisa lost all of its artistic merit, it’s also lost the metaphorical substance of its original self, having been transformed instead, over time, into a representation—not of the enigma in a woman’s smile, but—of cliché! The idea that a gesture repeated incessantly over time deflates it of its original meaning and creates a self-referential singularity was brushed upon by Duchamp during a 1961 interview:

I had the idea that a painting cannot, must not be looked at too much. It becomes desecrated by the very act of being seen too much. It reaches a point of exhaustion. In 1919, when Dada was in full blast, and we were demolishing many things, the Mona Lisa became a prime victim.24Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 2nd rev. ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1970), 477.

We may conjecture that in mustachifying La Joconde, Duchamp launches a three-pronged attack against 1) the standards of art at the turn of the century, 2) the Mona Lisa’s inherent semiosis, and 3) cliché itself. In other words, L.H.O.O.Q., can be interpreted as a commentary on art, the Mona Lisa, and cliché.

Duchamp’s act of artistic vandalism also occurs on several layers: the most obvious is, of course, the physical defacement of the Mona Lisa with graphite. The second most obvious is the addition of the new title, quite literally adding insult to injury. But a more surreptitious attack is the act of choosing a cheap postcard—a mass-produced object, virtually identical to hundreds, perhaps thousands, more—as the container for that vandalism. In so doing, Duchamp exposes a fragile and precarious tension between Capitalism and fine art:

Does commodification accelerate

Alas!

For the third time in this article, it is with un soupçon de chagrin that I inform Dear Reader that a deeper discussion of that question goes, perhaps predictably, beyond the scope of this article. One could argue, however, that Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q.—along with the other Readymades—was the match that lit the fuse to the powder keg of Postmodernism, a fuse that would be even further inflamed by Pop Artists such as Andy Warhol and Marjorie Strider.

• • •

In any case, a keen, poignant irony befalls L.H.O.O.Q. when examined within the cultural context of the present day. As the spirit of Dada permeated the art world, L.H.O.O.Q. became reiterated again and again as a symbol for the destruction of traditionalist artistic values. Variations on the work—some by Duchamp himself, including a non-mustachio’d Mona Lisa reproduction entitled simply L.H.O.O.Q Shaved (1965)—began to spring from the fertile minds of artists engaging with this new question of what art could be. With each such recasting, however, L.H.O.O.Q.’s symbolism gradually began to transmute, self-contextualize, and swallow itself up.

Salvador Dalí’s Self Portrait as Mona Lisa (1954)—a second order embedding of the Mona Lisa, i.e., the Mona Lisa embedded within L.H.O.O.Q. embedded within Dalí’s Self Portrait—is a prime example. As the title suggests, the work is a reproduction of La Gioconda but with Dalí’s face, including his trademark mustache, expertly substituted for the original. Mononymic Icelandic artist, Erró, allegedly “incorporated Dalí’s version of L.H.O.O.Q. into a 1958 composition,”25Wikipedia, s.v. “L.H.O.O.Q.,” last modified 12 January 2021, at 13:49 (UTC), accessed 18 Jan 2021.

Caveat lector: beyond the sentence quoted above, I have been unable to find a reliable source or example of the work in question. thus creating a third order embedding of Da Vinci’s original.

The parody became the parodied.

(Post-)Postmodernism; or, The Death of Irony

What was once a scathing polemic against the paragon of cliché in Western Art transformed into an emblem of cliché itself! To reinvoke Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q. became “desecrated by the very act of being seen too much.” It reached a “point of exhaustion,”26Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 477. to where here, now—some 100 years since the first faint fleck of follicular fuzz filled the enigmatic lip of La Joconde—yet another parody of L.H.O.O.Q. would be a cliché in itself.

While this unfortunate paradox seems to imply that Duchamp failed in his original goal—to strike down the obsolescent ikons of orthodoxy—, one might argue that he would have absolutely loved it this way: his specimen of anti-art was so anti-art that it became art in the most extreme degree, thus losing its artistic merit, and once again becoming anti-art. One might even describe L.H.O.O.Q. not as a physical work of visual art, but as a cultural experiment, a 100-year-long piece of performance art in which the performer is not a person, but an idea—a goatee on the Mona Lisa—and the performance is that idea’s metamorphosis though time, from devastating irony to stale, chalky sincerity.

Although the slow æsthetic evolution-degradation represented in L.H.O.O.Q’s journey through time might have been delightfully poignant for Duchamp, for the rest of us, here in , it lays bare a distressing truth:

In trying to get away from cliché, the gesture of ironically deploying cliché has itself become self-referential!

• • •

“I only use cliché ironically,” is, quite obviously, a specious claim, one as dubious as any twenty-first century Hipster’s pretense of originality. The false individuality of the Hipster subculture is a phenomenon many of us know well: their ostensibly sincere-ironic attacks on the mainstream begin to decay and re-pixelate into insincere-irony when viewed within a larger cultural context, one in which the Hipster-in-question conforms to a stereotype so thoroughly embedded, and endlessly satirized, in today’s cultural milieu, that it bears no real difference from the mainstream—i.e., that which the Hipster originally purported to eschew.

This ouroboric problem, in which irony consumes its own tail, occurs for the artist as well. When the act of fourth wall-breaking becomes so embedded in a certain cultural context that the audience can’t tell whether the wall being broken is a “real” fourth wall—separating the audience from the artistic artifact—or a “fake” fourth wall—a fictional, invented, expected, meta fourth wall that still exists within the artistic artifact, the expectation game is destroyed, and the very act of invoking irony becomes a stock gesture that opens up its own autoanamnestic memory rift.

The recursive fourth wall-breaking that has transformed Postmodernism’s “sincere-irony” to

You’ve got to understand that this stuff has permeated the culture. It’s become our language; we’re so in it we don’t even see that it’s one perspective, one among many possible ways of seeing. Postmodern irony’s become our environment.27Larry McCaffery and David Foster Wallace, “An Expanded Interview with David Foster Wallace,” in Conversations with David Foster Wallace, ed. Stephen Burn (Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 48-49.

In other words, if you’re living in a cultural ecosystem in which nothing is taken seriously, then your pointing out that something shouldn’t be taken seriously won’t be taken seriously! Partly because no one takes anything seriously in the first place, and partly because the act of ironic satirization is so deeply embedded in that culture that it has become so self-referential as to be gesturally, æsthetically emaciated.

Will Schoder provides an excellent summary of Wallace’s concerns with irony in the

This dystopian image of

What’s been passed down from the Postmodern heyday is sarcasm, cynicism, a maniac ennui, suspicion of all authority, suspicion of all constraints on conduct, and a terrible penchant for ironic diagnosis of unpleasantness instead of an ambition not just to diagnose and ridicule but to redeem.28McCaffery and Wallace, “Expanded Interview”, 48-49.

While the broader, everyday implications of this sociological schema go beyond the—now proverbial—scope of this article, they are somewhat alarming, especially as such notions as “suspicion of all authority” and “manic ennui” begin to hybridize with the anti-intellectualism of post-truth social media, “in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”29OED Online, s.v, “post-truth, adj.”, accessed 31 Jan 2021. The seeming futility of irony to adequately speak truth to power in the age of Twitter and The Masked Singer has been discussed by many, notably Michael Hirschorn in New York mag on the tenth anniversary of 9/11:

When facts are made stupid things and there is no coherent center to mediate truth, most irony starts falling on deaf ears because there is no lingua franca—the reference points are fuzzy, or the jokes hit but without breaking skin.30 Michael Hirshorn, “Irony, The End of,” New York, 27 Aug 2011.

The mutant offspring of reality-competition-show and reaction-video, The Masked Singer is, in my view, the epitome of the decay of Postmodernism into “manic ennui.” There are too many broken fourth walls to count: reality merges with surreality. In the end, the viewer’s mirror neurons are luridly inflamed as they watch an audience react to celebrities who react to celebrities in ostentaious, dystopian animal suits (relevant clip begins at 0:15).

Everything becomes a floating signifier.

• • •

But don’t despair!

Although it seems that we began exploring æsthetic distancing only to have it implode upon itself paragraphs later, all we’ve done is taken that idea to its extreme. And though the results of our investigation may seem like useless trinkets of nihilism, when held up to the light, they all reveal a deeper, vital truth:

Ironic meta-reference is neither a silver bullet nor a get-out-of-jail-free card nor a panpharmacon to the pox of cliché. When deployed poorly, even the stalwart bulwarks of irony metamorphose and moulder into dimensionless self-reference. But is irony—as Wallace or Hirschorrn might argue—dead? Schœnberg is dead. God is dead. Carter is dead. Boulez is dead. Irony?

Irony is not dead.

At least this composer doesn’t think so. Postmodernism—and, by extension,

Postmodern ideas are constantly ebbing and surging through our dynamic cultural milieu, as are

For ironic meta-reference to not itself distort into cliché, it must be deployed creatively—as one would do with any other creative technique—to communicate the artistic impulse. Works of

• • •

In other words, ironic meta-reference remains a powerful artistic tool, but it alone is not a formula for deploying cliché successfully every single time—nor does such a formula exist. As previously illustrated, a gesture’s self-referentiality is dependent upon its cultural context—a context that is constantly, insatiably in flux. Thus, there is no guarantee that any given strategy for effectively deploying cliché will retain its semiotic zest after any given amount of time or in any given situation.

Still, despite its capricious sillage, we cannot ignore the implacable aromatic potency of meta-reference to bring cliché to its knees. Nor can we overlook a second, perhaps more subtle technique for deploying and retaining agency over cliché—one that requires us to return to our cliché-as-singualrity metaphor and evert its black holes.

Black Hole: A Return to Semiotic Singularity

At the end of the day, the problem with clichés is that they mean too much!

Powerful, ancient, massive nodes of meaning, they lie in wait, each one asymptotically bending its local semiotic spacetime such that any innocent, hapless relationship-thread in its vicinity is captured in its gravity well, doomed to curve inward past the event horizon and become lost in an endless cascade of autoanamnestic self-reference.

A bleak fate.

But, let’s take a step back and re-evaluate that metaphorical scenario more carefully, sans poetic flair: the cliché bends its local semiotic spacetime inward toward itself. Its local spacetime. The locality of the semiotic singularity is the conceptual keystone that when removed collapses bastion into dust.

• • •

Consider first the scenario above: imagine yourself as a relationship thread—or, rather, imagine yourself at the end of a thread tracing a straight path through semiotic space in search of a node on which to attach. As you travel though this endless isotropic expanse, toward some far-off destination, you pass by many semiotic constellations—galaxies of language, solar-systems of conceptual frameworks, globular clusters of related ideas—all of which are glorious to behold, but are neither close enough nor massive enough to draw you toward them.

As you continue traveling through this space, however,—at the speed of thought—you realize that a seemingly empty patch ahead of you has grown considerably larger, and constellations of meaning nodes beyond have begun to distort, eventually blinking out entirely. What you originally thought was empty space is in fact a mass of pure dark, a singularity, a cliché.

Hurtling relentlessly toward the colossus of spiraling self-reference, with no way to slow or swerve, you may rest assured that there is no need to worry about falling in—mainly because we already talked about falling in in the last article. Instead, this thought experiment is more concerned with what happens as you skirt past it.

Traveling in a straight line with the singularity off to your left, it begins to act on you with an attractive force, as though a giant invisible tether has formed between you and the cliché, swinging you around its axis. You begin to curve in its direction, but since you weren’t close enough to fall through the event horizon, you’re released from its gravitational influence and continue along your journey—shaken, but alive.

Note how the cliché bends semiotic spacetime (here represented by only two spatial dimesnions).

Caught in its gravitaional drifts, the path traced by our relationship-thread is diverted.

Removing ourselves temporarily from the prospective perspective of the relationship-thread’s traveling tip, we may examine the path we just traced through semiotic spacetime: we began moving in a straight line, curved left, and then continued straight. If we rewind and replay the thought experiment with the singularity to our right, or above us, or below, we’d curve that way instead. Simple enough.

In fact, why don’t we replay the experiment? We’ll rinse and repeat, but with one key difference: instead of encountering one black hole along our journey we will imagine that we encounter two. The first black hole will be in the same place it was the first time, immediately to our left. But the second will be a reflection of the first—exactly the same size and in exactly the same place, except to our right. And as we advance directly toward both of them, our path will be aligned to pass exactly between the two.

Back in the driver seat of our itinerant axon, we make our approach. And since we are constantly perfectly equidistant from both singularities, they both exert upon us an equal semiotic pull. Aside from a small acceleration-deceleration as we pass between the two devowering stars, we don’t notice a thing, and the path we trace remains uncruved, unzigged, unzagged.

Delightful.

Unfortunately, the double-cliché experiment is an exceptionally idealized model of an extremely unstable scenario: as we traverse the void between the two singularities, we need to remain precisely equidistant from both of them to keep the net semiotic attraction at zero. The slightest perturbation and our relation-thread goes careening off toward—or worse, into—one of them. And since the semiotic gravity of each cliché is stronger the closer you are to its centroid, as you near them your path becomes more and more precarious—as though, in attempting to thread a needle, the needle’s eye constricts to an infinitesimal point with the approach of the thread.

An illustration of the Double Cliché Experiment, threading the gravitational needle.

Let’s stop once again; rewind to the beginning. When we added a second singularity to our system, the path we were able to trace with our relationship-thread became straight, albeit extremely precariously so. If two singularities (dubiously) straightened the path of our relationship-thread, what would happen if we added more? Would three singularities make the system more stable? What about four? Six? Three-hundred and seventy-one? The further we take this line of thought, the more we realize that—as we add more and more singularities to our model—while this does create new routes of asemiosis through our rhizomatic expanse, they are all equally unstable.

What we need is a way to cancel out the semiotic effect of all of these singularities—everywhere and all at once. But every time we introduce a new singularity to do so, we create new imbalances into which our semiotic space implodes. So the question becomes:

How may we conceive of a semiotic spacetime in which embedded clichés—objects of infinite semiotic density—cancel each other out, but in a way that doesn’t create instabilities in the very fabric of the meaning-space?

To answer this, we need to go back, back to the beginning.

The beginning of the universe.

Big Bang: Hypercontextualization as a Means of Asemiosis

Most of us are familiar with the scientifically verifiable creation myth of our home universe, namely The Big Bang. Paradoxically, it was neither a bang34Professor Philip Moriarty, University of Nottingham: “Actually it was silent.” Brady Haran, “How loud was the Big Bang?,” Sixty Symbols, 1 Aug 2018, YouTube video, 13:40. Relevant passage at timestamp 1:39. nor was it big: the theory is a set of descriptions that detail “how the universe expanded from an initial state of extremely high density…preceded by a singularity in which space and time lose meaning.”35Wikipedia, s.v. “Big Bang.”

A widely accepted model within the Big Bang theory is a period of extremely rapid exponential expansion known as Inflation that cosmologists believe lasted “from 10−36 seconds after the conjectured Big Bang singularity to some time between 10−33 and 10−32 seconds after the singularity.”36Wikipedia, s.v. “Inflation (cosmology).” For fear of getting too engnarled in the weeds of this subject, suffice it to say that our current “observable universe, at the end of a period of inflation, would be about the size of a grapefruit.”37Brady Haran, “Inflation & the Universe in a Grapefruit,” Sixty Symbols, 1 Dec 2013, YouTube video, 24:07. Interview with Professor Edmund Copeland, University of Nottingham. Relevant passage at timestamp 13:53. In other words, everything that we have ever known to exist at one point occupied a volume only a few centimeters in diameter. Why, then—with so much energy concentrated into so small a volume—did our nascent universe not immediately collapse into a black hole?

The answer to this question strikes at the heart of our dilemma: according to George Musser, contributing editor for Scientific American,

Black-hole formation actually depends on the variation in density from one place to another—and there was very little variation back then. Matter was spread out almost perfectly smoothly.38George Musser, “According to the big bang theory, all the matter in the universe erupted from a singularity. Why didn’t all this matter—cheek by jowl as it was—immediately collapse into a black hole?,” Scientific American, 22 Sep 2003, accessed 18 Feb 2021.

In other words, it was the lack of a density gradient—local imbalances—that effected the absence of a total gravitation collapse.39The physicists among you may contend that this is an oversimplification, as it ignores the necessity of an expanding spacetime to prevent black hole formation. And you’d be absolutely right. The scope of this description, however, is limited to its ability to help us problem solve within the metaphorical domain of our semiotic spacetime. To learn more deeply about the behavior of actual, real-world spacetime, I refer interested parties to Albert Einstein’s field equations. If every single point in spacetime has extremely high energy density, bending space toward itself, there is a net bend of zero.

Transposing this idea to our semiotic spacetime imparts a solution: it does us little good to infuse our model with a finite—albeit arbitrarily large—number of semiotic singularities acting fruitlessly to unbend the local meaning-space distorted by the original cliché. Rather, we need an infinite number of semiotic singularities, one for every single point in our unbounded semiotic spacetime. What’s more, these singularities must be identical in size and construction to preclude the formation of a significant semiotic density gradient.

Thus we may imagine a semiotic spacetime perfused with an infinite number of identical clichés at every point—both rational and transcendental—all pulling on each other in concert, cancelling each other out. Such a spacetime would be taut, viscous, sinewy—but stable! And through such a meaning-space—made once again homogeneous, isotropic—our relationship-thread may freely wander and rove.

• • •

As if the actualization of some cosmological inevitability, this description of a cliché hypercontextualized by countless other identical copies of itself bears us back to the beginning of our journey, to when we codified the last of four generalizations on symbols, context, and meaning:

Meaning exists at the nexus of differences between signs. If a Semiotic rhizome is composed only of similarities between identical signs, parallel lines in divergent space, then there aren’t enough relationships between the signs to confer upon them distinct meaning….

4. A self-contextualized symbol behaves like a floating signifier.40Miggy Torres, “Understanding, Harnessing, and Annihilating Cliché,” What Can Choral Music Be?, accessed 18 Feb 2021.

Here we exit our abstract model of semiotic cosmology and re-enter the world of the concrete: just as the word word was previously stripped of its meaning when hyperselfcontextualized, so, too, can Onceuponatime or an itinerant Water Lily be drained of its power. A Onceuponatime hypercontextualized with infinite Onceuponatimes—cast into its own autoanamnestic mirror world—knows not who it is, why it’s there, what it wanted, where and when it came from, how to get back, and whether it even exists as anything more than a memory-echo of itself.41Miggy Torres, “Cliché, Singularities, and Infinite Echolalia,” What Can Choral Music Be?, accessed 18 Feb 2021.

Of course, in real life, we cannot create an infinite number of objects or gestures in a work of art, nor should we be expected to. The cliché-as-singularity metaphor is exactly that: a metaphor. When literalized and applied to our artistic practice, infinite gestures inevitably become finite. That said, the difference between finity and infinity may really be a matter of point of view.

Each work of art is a window into a new reality, and as we stand on the outside looking in, that which is literally finite to our ears and eyes may be metaphorically infinite within the bubble universe of the work of art. Thus, rather than attempting in vain to infuse a work of art with infinitely many brush strokes or musical notes, we may simply saturate the meaning-space of the work of art with spectres of the original cliché, rendering it more and more powerless.

Now a floating signifier, drained of its power, desperate for a meaning-node onto which to latch, the cliché may now, finally, be given new meaning by the artist.

• • •

But beware! Even dead clichés leave traces, semiotic ghosts that whisper to us in the Post-postmodern tongue. Even this technique of hyperselfcontextualization can itself become cliché. And, just as with Meta-reference, it is not a panacea, but simply another option to be deployed creatively—with purpose—by the artist.

The way up and the way down is one and the same.

The methods described here for harnessing cliché are only two of many possible treatments and techniques that I’ll leave the reader to discover on their own. Indeed, Meta-reference and Hypercontextualization may themselves one day become irredeemably cliché, and new modes of manipulation will need to be discovered.

Clichés are a varied and diverse phylum of beasts: what may be the paragon of originality to me may be irreformably cliché to you. There are families of cliché with varying degrees of self-referential gravity. There are genera that are only clichés in certain contexts but not in others (e.g. at the beginning of a piece vs. at the end of one). And because the cliché’s self-referentiality is born from its relationship with the cultural context in which it’s embedded, its power as a cliché will also vary depending on the level of familiarity the listener has with that—ever evolving—cultural context (which includes the repertoire).

A cliché looms amid a rhizomatic semiotic network.

Ezra Pound believed that, just as old works of art influence artists today, works created today can influence works past, that artistic influence did not follow the arrow of time. Poetry scholar Langdon Hammer waxes lyrical:

There are no dead forms. There are no dead languages. There are only derivations, variations, translations through which the past is continuously being made present….

…[The artist is] a mediator, conducting a process by which the sources of the past are brought forward into the future, relaying, what [Pound] calls, the impulse, and in the process, making it new….42Langdon Hammer, “9. Ezra Pound,” YaleCourses, 6 Dec 2012, YouTube video, 52:03. My italics. Relevant passages at timestamps 29:10 and 51:20.

For Pound, the past is something that can be reembodied continually, and needs to be reembodied continually, over and over again in new forms. In this sense, [the act of] translation envisions a past that is metamorphic.43 Langdon Hammer, “10. T.S. Eliot,” YaleCourses, 6 Dec 2012, YouTube video, 49:46. My italics. Relevant passage at timestamp 5:53.

Here, Hammer contrasts the act of translation with the act of quotation, which—rather than transforming—preserves or parodies the past. I am acutely aware of the irony of quoting this passage verbatim, but a paraphrase would not do justice to Hammer’s eloquence.

Thus, it is up to the artist in the end to engage firmly, confidently, authetically with their own cultural context: its present, its past, its future. Some haggard gestus from days gone by may become reinvigorated by a steadfast painter’s brush. Some flacid trope may effloresce at the hand of a sculptor of sound or stone. What was once cliché can be reformed, recontextualized, made innovative. And what was once the apotheosis of chic may be brought low by the unending flow of time.

Cheers.

• • •

Notes

1 Though neither bolded nor italicized, the word “original” is key to this idea. It would do the artist little good to seek shelter from one cliché by leaping into the gaping maw of another. More on this problem later in the article.

2 Werner Wolf, “Metareference across Media: The Concept, its Transmedial Potentials and Problems, Main Forms and Functions,” in Metareference across Media: Theory and Case Studies, ed. Werner Wolf, Katharina Bantleon, Jeff Thoss, and Walter Bernhart, (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009), 31.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 The exact English rendering of this agglutinous German word is a matter of some disagreement.

6 That is to say, dissonance between media (i.e., music and some other medium) in the multimedia (in this case, theatrical) work—e.g., quirky, jolly music and dance paired with harrowing text about the need to prostitute oneself or face starving to death. This not to be confused with dissonance between elements within a single medium—e.g., harmonic dissonance, melodic angularity, poetic enjambment, slant rhyme, narrative tension, complementary colors, etc. For more on consonance and dissonance between musical and non-musical media, I, once again, recommend Daniel Albright’s Untwisting the Serpent.

7 b e y o n d t h e s c o p e

8 “The moon’s an arrant thief, / And her pale fire she snatches from the sun;”

William Shakespeare, Timon of Athens, in Timon of Athens, ed. Anthony Dawson and Gretchen Minton (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2008), 1.3.432-433. References are to act, scene, and line, accessed January 9, 2021, http://dx.doi.org/

9 Nancy Lewis Tuten and John Zubizarreta, The Robert Frost Encyclopedia (Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 2001), 297-280.

10 “Bucolic realism.” If you’re chic,

You might say “réalisme bucolique”.

11 Vladimir Nabokov, “Pale Fire,” in Pale Fire: a Novel (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1989), lines 423-426.

12 Two lines that rhyme with five iambs in each

Just like the ones in this affected speech.

13 Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. “Heroic Couplet,” accessed January 10, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/

14 Nabokov, “Pale Fire,” in Pale Fire: a Novel, lines 703-707.

15 For truth, to be precise we may contrive

The rhythm here, in fact, is three on five.

16 Grove Art Online, s.v. “Ready-made,” by Matthew Gale, accessed 12 Jan 2021, https://www-oxfordartonline-com.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000070990.

17 “Asked in an interview, ‘What is a readymade,’ Duchamp’s first response was to laugh. When this laughter subsided, he gave an example: Mutt’s Fountain. Asked to expand upon the matter, he turned to other possibilities for readymades. He noted that there was the ‘assisted readymade’ (ready-made aidé), and gave as an example his mistreated Mona Lisa.”

Leland de la Durantaye, “Readymade Remade: Pierre Pinoncelli and the legacy of Duchamp’s ‘fountains,’” Cabinet, Fall 2007, https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/27/durantaye.php.

18 Notably: Pure Readymades, objects unaltered by the artist; Assisted Readymades, objects made by combining two or more pre-existing objects; and Rectified Readymades, objects to which some traditionally-artistic medium has been added (e.g., oil paint, graphite, gouache, etc.).

19 Encyclopædia Britannica considers Fountain to be a so-called Pure Readymade*, while Grove Art Online states that it may be considered an Assisted Readymade due to the signature “R. Mutt” applied to the work.† The application of paint to the piece, however,—as opposed to its combination with some other pre-made object—would seem to designate it a Rectified Readymade. Even the work in question, L.H.O.O.Q., is regarded by Grove Art Online and the Norton Simon Museum‡ as a Rectified Readymade, while Duchamp himself has been quoted describing it as Assisted (see note 17)! In the end, it’s clear that the exact taxonomy of these objects is subjective and completely beside the point: such classification serves not to impose a rigid labeling system upon a diverse group of works created before such a system was even considered by the artist, but to simply highlight for the viewer—subjectively—certain differences among the objects that may aid with their æsthetic interpretation.

* Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. “Ready-made,” accessed 12 Jan 2021, https://www.britannica.com/art/ready-made.

† Grove Art Online, “Ready-made.”

‡ “L.H.O.O.Q. or La Joconde,” Norton Simon Museum, accessed 12 Jan 2021, https://www.norton

20 The phrase Elle a le feu au cul—literally meaning “her ass is on fire”—is the more common variant of this vulgarism,§ but if the chaud fits, wear it.

§ Wiktionary, s.v. “avoir le feu au cul,” accessed 16 Jan 2021, https://en.wiktionary.org/

21 No pun here, folks. Carry on.

22 Paul N. Humble, “Anti-Art and the Concept of Art,” chap. 19 in A Companion to Art Theory, ed. Paul Smith and Carolyn Wilde (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), 247.

23 Ibid.

24 Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 2nd rev. ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1970), 477.

25 Wikipedia, s.v. “L.H.O.O.Q.,” last modified 12 January 2021, at 13:49 (UTC), accessed 18 Jan 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L.H.O.O.Q. Caveat lector: beyond the sentence quoted above, I have been unable to find a reliable source or example of the work in question.

26 Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 477.

27 Larry McCaffery and David Foster Wallace, “An Expanded Interview with David Foster Wallace,” in Conversations with David Foster Wallace, ed. Stephen Burn (Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 48-49.

28 McCaffery and Wallace, “Expanded Interview”, 48-49.

29 OED Online, s.v, “post-truth, adj.”, accessed 31 Jan 2021, https://www-oed-com.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/view/Entry/58609044.

30 Michael Hirshorn, “Irony, The End of,” New York, 27 Aug 2011, https://nymag.com/

31 Mas’ud Zavarzadeh and Donald Morton, Theory, (Post)Modernity, Opposition: An “Other” Introduction to Literary and Critical Theory (Washington, DC: Maisonneuve Press, 1991), 108.

32 Jonathan D. Kramer, Postmodern Music, Postmodern Listening, ed. Robert Carl (Bloomsbury Academic: New York, 2016), 6. I would be remiss not to recommend this title—a tour-de-force exploration of Postmodernism in music, edited by my colleague, composer Robert Carl—to Dear Reader in full.

33 Not, to my knowledge, a technical term.

34 Professor Philip Moriarty, University of Nottingham: “Actually it was silent.” Brady Haran, “How loud was the Big Bang?,” Sixty Symbols, 1 Aug 2018, YouTube video, 13:40, https://youtu.be/KYr6Yjol3xM. Relevant passage at timestamp 1:39.

35 Wikipedia, s.v. “Big Bang,” https://en.wikipedia.org/

36 Wikipedia, s.v. “Inflation (cosmology),” https://

37 Brady Haran, “Inflation & the Universe in a Grapefruit,” Sixty Symbols, 1 Dec 2013, YouTube video, 24:07, https://youtu.be/m7C9TjdziPE. Interview with Professor Edmund Copeland, University of Nottingham. Relevant passage at timestamp 13:53.

38 George Musser, “According to the big bang theory, all the matter in the universe erupted from a singularity. Why didn’t all this matter—cheek by jowl as it was—immediately collapse into a black hole?,” Scientific American, 22 Sep 2003, accessed 18 Feb 2021, https://www.scientific

39 The physicists among you may contend that this is an oversimplification, as it ignores the necessity of an expanding spacetime to prevent black hole formation. And you’d be absolutely right. The scope of this description, however, is limited to its ability to help us problem solve within the metaphorical domain of our semiotic spacetime. To learn more deeply about the behavior of actual, real-world spacetime, I refer interested parties to Albert Einstein’s field equations.

40 Miggy Torres, “Understanding, Harnessing, and Annihilating Cliché,” What Can Choral Music Be?, accessed 18 Feb 2021, https://www.miggytorres.com/

41 Miggy Torres, “Cliché, Singularities, and Infinite Echolalia,” What Can Choral Music Be?, accessed 18 Feb 2021, https://www.miggytorres.com/

42 Langdon Hammer, “9. Ezra Pound,” YaleCourses, 6 Dec 2012, YouTube video, 52:03, https://youtu.be/

43 Langdon Hammer, “10. T.S. Eliot,” YaleCourses, 6 Dec 2012, YouTube video, 49:46, https://youtu.be/eUO-ICj6PHQ. My italics. Relevant passage at timestamp 5:53. Emphasis mine. Here, Hammer contrasts the act of translation with the act of quotation, which—rather than transforming—preserves or parodies the past. I am acutely aware of the irony of quoting this passage verbatim, but a paraphrasewould not do justice to Hammer’s eloquence.